CASE20250818_005

Trapped!: Unexpected Complications During a Routine PCI

By Ying-Chien Wang

Presenter

Ying-Chien Wang

Authors

Ying-Chien Wang1

Affiliation

Changhua Christian Hospital, Taiwan1

View Study Report

CASE20250818_005

Complication Management - Complication Management

Trapped!: Unexpected Complications During a Routine PCI

Ying-Chien Wang1

Changhua Christian Hospital, Taiwan1

Clinical Information

Relevant Clinical History and Physical Exam

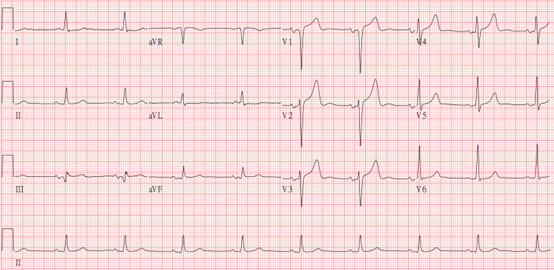

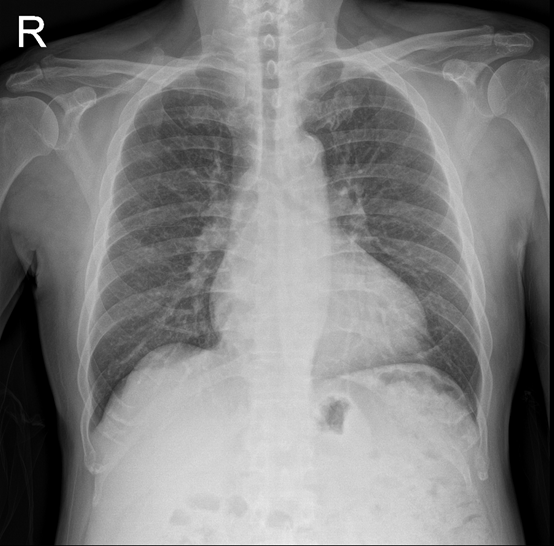

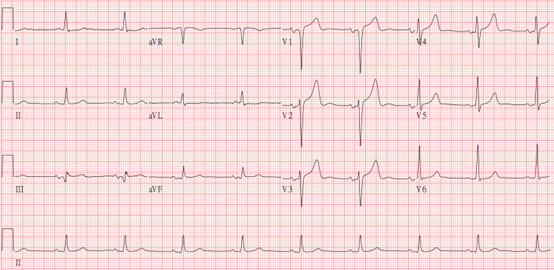

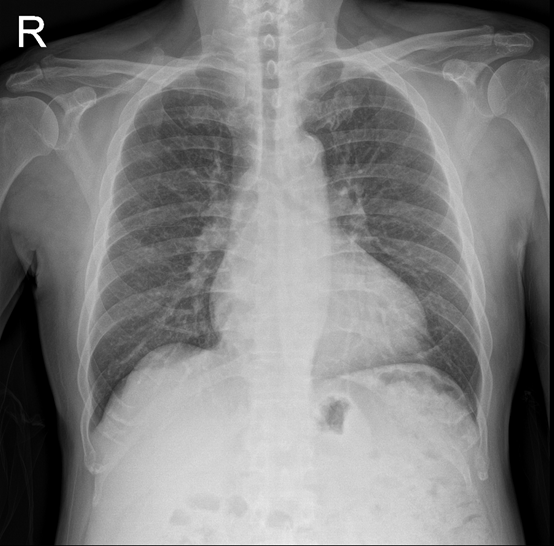

A 59-year-old man with dyspnea on exertion for a month was admitted for scheduled percutaneous coronary intervention. His medical history included hypertension, hyperlipidemia, and type 2 diabetes. He also had 2-vessel coronary artery disease with a bare metal stent each in the right coronary and the left anterior descending arteries. Physical examination was unremarkable except for being slightly overweight; ECG showed sinus bradycardia and chest x-ray excluded severe pulmonary disease.

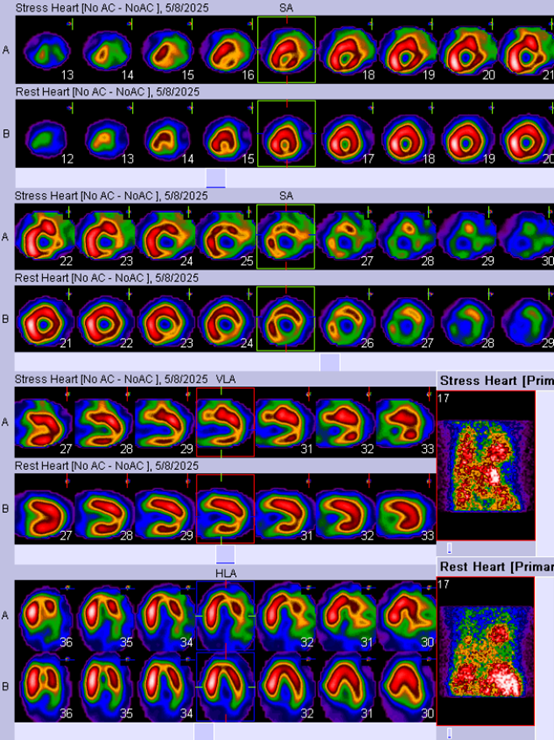

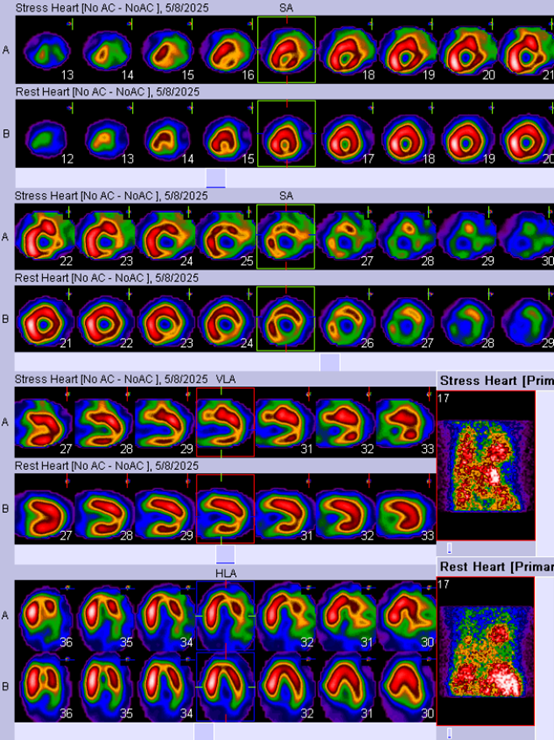

Relevant Test Results Prior to Catheterization

Laboratory findings indicated no blood dyscrasia; liver/renal function tests were within normal limits, and there was no electrolyte imbalance. Myocardial perfusion scan found an ejection fraction of 50% both at rest and during stress; the test also suggested that there were possible lesions affecting all three coronary arteries.

Relevant Catheterization Findings

Coronary angiogram found 50-60% out-of-stent stenosis at proximal left anterior descending artery and 89-90% stenosis at the proximal left circumflex artery (LCx). The right coronary artery was completely occluded, with collaterals from LCx supplying the posterior descending and posterolateral arteries.

Video1_RCA_1.wmv

Video1_RCA_1.wmv

Video2_RCA_2.wmv

Video2_RCA_2.wmv

Video3_Collaterals.wmv

Video3_Collaterals.wmv

Interventional Management

Procedural Step

With an AL-1 short-tip guiding catheter in the right coronary artery (RCA) and several guidewire escalations, under the support of a Caravel microcatheter. We eventually penetrated the proximal cap with a Gaia 2 wire, then switched to a XT-A. An EBU 3.5 guiding catheter was placed in the left coronary artery to perform bidirectional injection, which confirmed successful crossing of the distal cap.

We removed the Caravel microcatheter using a Conquorer 2.5*12 mm trapping balloon. However, there was difficulty advancing a 2.0 mm angioplasty balloon, and we noted that the tip of the Caravel catheter had broken off. Buddy-wire technique failed to retrieve the fragment. Because the calcified lumen was too narrow for equipment manipulation, we decided to risk fragment migration from increased blood flow and dilated the vessel.

Further attempts with a 4 mm snare and balloon-trapping with a 2.0 mm balloon both failed, despite additional support from a guiding extension catheter. Finally deciding to leave the fragment in situ, we completed angioplasty with two drug-eluting balloons. As we removed the guidewire, we noted that the fragment also withdrew along with the wire.

We managed to bring the fragment out of the vessel; however, it bumped against the aortic wall and dislodged into the systolic blood flow. After carefully monitoring the patient for two more days, he was discharged home after we confirmed that he exhibited no overt thromboembolic sequelae.

Video4_Caravel_Removed.wmv

Video4_Caravel_Removed.wmv

Video5_Fragment.mp4

Video5_Fragment.mp4

Video6_Dislodge.wmv

Video6_Dislodge.wmv

We removed the Caravel microcatheter using a Conquorer 2.5*12 mm trapping balloon. However, there was difficulty advancing a 2.0 mm angioplasty balloon, and we noted that the tip of the Caravel catheter had broken off. Buddy-wire technique failed to retrieve the fragment. Because the calcified lumen was too narrow for equipment manipulation, we decided to risk fragment migration from increased blood flow and dilated the vessel.

Further attempts with a 4 mm snare and balloon-trapping with a 2.0 mm balloon both failed, despite additional support from a guiding extension catheter. Finally deciding to leave the fragment in situ, we completed angioplasty with two drug-eluting balloons. As we removed the guidewire, we noted that the fragment also withdrew along with the wire.

We managed to bring the fragment out of the vessel; however, it bumped against the aortic wall and dislodged into the systolic blood flow. After carefully monitoring the patient for two more days, he was discharged home after we confirmed that he exhibited no overt thromboembolic sequelae.

Case Summary

This is a scenario with several learning points. First, a trapping balloon may fragment a microcatheter tip even with appropriate techniques. Second, before attempting retrieval, we should first confirm whether the fragment was still on the wire. If still on the wire, we could push the guiding extension catheter further, and brought the fragment into the catheter, then employed suction to retrieve it with much less risk and effort. There is also the dilemma of dilating the vessel for retrieval maneuvers at the risk of dislodging the fragment further. By presenting this case for discussion, we hope we would all avoid being trapped by such complications in the future.